A Guide to the Worst Presidential Campaigns Ever

in Writing on Tufts, Blog posts

The debates are starting, the apple cider is warming, and it’s election season here at Tufts! That means it’s time for me to break myself away from the 2012 candidates (and my homework) and take a long, hard look back at the candidates who have come before. Who was a bad campaigner? Who was simply stupid? Who had an extramarital affair on board a yacht called Monkey Business?

The answers are below, in Evan’s 2012 Guide to the Worst Presidential Campaigns Ever!

(Keep in mind that this list is by no means definitive, and you have every right to disagree with me. In fact, please disagree with me! I’m an economics major who looked up a lot of this information in books and on the internet; if you think I was wrong to classify one candidate as a flop while you think he’s a tragic hero, write it in the comments!)

Runners-up: Aaron Burr, Al Gore, Robert Taft, Duncan Hunter, Howard Dean, Gerald Ford, George H.W. Bush, Horace Greeley, Alton Parker, John Edwards, Thomas E. Dewey, Update: Hillary Clinton

- William H. Seward, 1860

William Seward, of Seward’s Folly (AKA Alaska) fame, ran for the Republican nomination for president in 1860. He had lined up so much support behind him and was so confident of winning the nomination that he left the country for 8 months before the party convention in 1859. Of course, it may also have been because he was worried that he might say something stupid or offend one or another faction (as he had when he declared that slavery, while legal under the constitution, was against a “higher law”). In any case, while Seward was in Europe and Asia (where he acquired several Arabian horses) a young man from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln managed to build up enough support to win the endorsement of the Republican Party. Seward eventually became Lincoln’s Secretary of State, so all’s well that ends well.

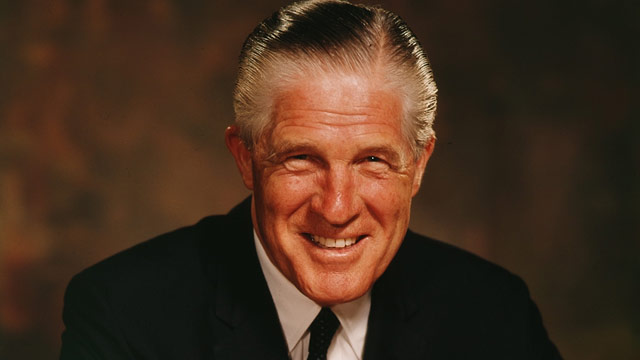

- George W. Romney (R-MI) 1964, 1968

Tell me, does this sound familiar: wealthy businessman and former Republican governor runs for president, appears as the front runner for a brief period, proceeds to make a series of flip-flops, has serious difficulty articulating a stance on foreign policy (or indeed any topic) and then refuses to give up when it’s very, very clear that he’s lost? Oh, and he’s Mormon.

Such was the situation in 1968, when former Michigan Governor George Romney, father of former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney ran for the Republican nomination against Richard Nixon (who eventually beat Hubert Humphrey in the general election).

Romney found it difficult to express an opinion on almost any issue, especially foreign policy. He famously said that he had been “brainwashed” by the US military into supporting the Vietnam War (“I was against it before I was for it”?) and often misspoke during interviews or press conferences. Romney was also famous for not expressing himself clearly on the issues, preferring, instead to explain himself at a later time (this is George Romney we’re talking about).

In 1968, Governor George Romney turned an 8% polling lead over Richard Nixon into a 26% deficit in only a few months, a feat few can match.

- Mike Gravel (D-AK) 1972, 2008

As a US Senator in 1972, Mike Gravel did not campaign for the presidency. He campaigned to become the vice president. According to the New York Times, Sen. Gravel began campaigning for second place on June 2, 1972, more than a month before his party’s nominating convention. He wasn’t even the only one running: the Democratic delegates in Miami Beach, Florida in 1972 nominated over 70 possible vice presidential candidates (including Mao Zedong) before settling on Senator Thomas Eagleton (see #7).

In 2006, Senator Gravel announced his intent to run for president in the 2008 elections at a press conference at the National Press Club (which he travelled to on public transportation, his campaign being short of funds).

In 2007, he released two campaign ads, titled “Rock” and “Fire,” that can only be described as “bizarre.” The former features Gravel staring into the camera for about a minute, then picking up a large rock and throwing it into a lake. Gravel actually said that it wasn’t an ad; it was a “metaphor of an ordinary citizen who acts in an unusual and extraordinary way.” It was certainly unusual.

Gravel continued to poll below 1% among Democrats, even hitting statistical zero in the Iowa caucuses, but he didn’t give up: he just switched parties. In March of 2008, Gravel announced that he would seek the Libertarian Party’s nomination for president, but that didn’t go so well, either. The Senator continued campaigning and eventually finished fourth of eight at the Libertarian convention.

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| George McGovern (D-SD) | Sargent Shriver | Thomas Eagleton (D-MO) |

- George McGovern (D-SD), Sargent Shriver, and Thomas Eagleton (D-MO) 1972

What happened in 1972? The numbers say that incumbent Republican President Richard Nixon won a landslide (and I do mean landslide) victory over Democratic challenger George McGovern, 520 to 17 (with one faithless elector) but that doesn’t even get close to the full story.

McGovern ran on a platform of withdrawal from Vietnam in exchange for American POWs and amnesty for draft-dodgers. He also supported higher taxes, more welfare, and the Equal Rights Amendment. Robert Novak reported in a column that an “anonymous Senator” (later revealed to be Thomas Eagleton of Missouri) had said that McGovern was “for amnesty, abortion and legalization of pot.”

In the run-up to the Democratic Party’s nominating convention in Miami Beach, Florida, McGovern scrambled to find a running mate. Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA) who had been considered a front-runner for the presidency until an incident with a woman, a car, and a bridge, declined to accept the spot of vice president, leaving Sen. McGovern in the lurch, as he had all but assumed Kennedy would leap at the opportunity and none of the other candidates wanted to be Veep either. Awkward.

McGovern felt that he needed a candidate to balance the ticket, so what did he do? Well, he did what candidates always do when they need a typecast VP, are struggling, have barely made it past the primary, and are facing a tough general election: he chose a running mate without vetting them. (see: McCain, John. 2008.)

Specifically, McGovern chose the very senator who had created the “candidate of amnesty, abortion, and acid” nickname: Senator Thomas Eagleton of Missouri. Eagleton actively disagreed with McGovern on many issues, was confirmed at almost 2am, and was an almost total unknown. The issue that ended his campaign, however, had nothing to do with his political beliefs: in the 1960s, Eagleton had received electroshock therapy for clinical depression, “manic depression,” and “suicidal tendencies,” a fact that he had not disclosed to (and in fact actively concealed from) McGovern or his campaign. When this came out, just two weeks after the convention, McGovern said that he would support Eagleton “1000%,” although senior Democrats began muttering about Eagleton’s ability to perform the duties of the vice president. Despite public support, McGovern decided that he couldn’t continue with Eagleton as his running mate, and on August 1st, 1972, Eagleton resigned as the nominee.

What followed wasn’t pretty. Six, count ‘em, six, Democrats very publically refused the nomination before the Ambassador to France and former Director of the Peace Corps, Sargent Shriver accepted it and was nominated by a special session of the DNC. McGovern went into “the Eagleton Affair” with a 41% approval rating. After the nomination of Ambassador Shriver two weeks later, he had a 24% approval rating.

You know what happened next: McGovern/Shriver ’72 went down in a fiery ball of indecisiveness and controversy and won only one state, spawning the famous post-Watergate bumper sticker: “Don’t blame me, I’m from Massachusetts.”

- Harold Stassen (R-MN) 1944, 1948, 1952, 1964, 1968, 1976, 1980, 1984, 1988, 1992, 1996, 2000

If your name becomes synonymous with “also ran,” you should probably reconsider your choice of career. Harold Stassen ran for president twelve times between 1944 and 2000, making him the butt of jokes from The Simpsons to Hunter S. Thompson books. The first few times, Stassen was actually fairly successful, coming in second place in primary polling in 1948 and receiving delegates as recently as 1968 (although one of his two that year was his nephew).

In later elections, not only did Stassen fail to garner any votes, but the humorous “Stop Stassen” movement began to attract more attention than his campaign, which is a kind of success, in a way. …I guess.

- Alf Landon (R-KS) 1936

Picture the country in the midst of the worst depression in history, a Great Depression, if you will. Picture government programs that are bringing you food, money, and work. Now picture a man who wants to get rid of them. That’s what many American’s had to do – picture Alf Landon – because the opponent of FDR’s New Deal policies made no campaign appearances – zero – in the two months after he was nominated on the first ballot at the Republican National Convention in 1936.

Landon, an oil millionaire and the sitting governor of Kansas, was known as a recluse, but had a reputation in the statehouse for balancing the budget and keeping taxes low. He did respect FDR, but he disagreed with the scope of the President’s ideas, calling many parts of the New Deal a “loss of economic freedom.”

Landon was such a bad campaigner and was so seldom seen on the stump that a columnist joked, “The Missing Persons Bureau has sent out an alarm bulletin bearing Mr. Landon’s photograph and other particulars, and anyone having information of his whereabouts is asked to communicate direct with the Republican National Committee.”

Landon was nominated more as a sacrificial goat than anything else: he lost his home state of Kansas and carried only Maine and Vermont, losing to Roosevelt 523 to 8.

- Strom Thurmond (D-SC) 1948

Hubert Humphrey convinced the Democrats to adopt a pro-civil rights platform for the first time at their 1948 convention, and it was embraced by the party establishment, including President Harry Truman, but it angered many southern Democrats, or “Dixiecrats.” In response to the adoption of the inclusive platform, the Dixiecrats endorsed Governor Strom Thurmond of South Carolina.

Of course, most campaigns have a slogan – a campaign line that is uniquely theirs. Barack Obama’s slogan in 2008 was “Hope,” and in 1976, Gerald Ford’s was “He’s making us proud again.” What was Strom Thurmond’s?

“Segregation forever.”

This is the man who said, “All the laws of Washington and all the bayonets of the Army cannot force the Negro into our homes, into our schools, our churches and our places of recreation and amusement,” conducted the longest filibuster in history against the Civil Rights Act of 1957, and served in the Senate until he was 100. When he said forever, he meant forever.

The Dixiecrats were adamant about states’ rights, especially when it came to denying rights to people they didn’t like. Unsurprisingly, Thurmond won almost all of his votes in southern states, but what is surprising is that he managed to win a few electoral votes in the process: the 39 electors of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and South Carolina were all pledged to him.

- John McCain (R-AZ), Sarah Palin (R-AK) 2008

John McCain was, by most accounts, a serious, experienced, and solid candidate. Most of the attacks on his campaign were actually on George W. Bush’s administration and the party that he had gathered around him. All McCain had to do was convince America that he wasn’t any of the things that Bush was, i.e. that he was actually the man that had cosponsored the McCain-Feingold Campaign Finance Reform Act, that he was level-headed, and, above all, that he didn’t have some questionably insane, gun-toting vice president up his sleeve.

Well, sh*t.

Sarah Palin was about as far off the mark as the McCain campaign could have shot (Dick Cheney may have been giving them lessons) and, as it became clear that the campaign hadn’t vetted her properly, sent the very clear message that the Republicans wanted in on the new trend of ballot diversity. It was a shot at middle-class, female voters, but it came off as cynical and desperate in the face of a seemingly unstoppable Obama campaign.

Even worse? Palin quickly went off-message and became the subject of ridicule for her interviews and YouTube clips. Saturday Night Live’s parody of Palin’s speeches became even more popular than the speeches themselves. Not a good sign.

Ultimately, McCain lost 365 to 173.

- Gary Hart (D-CO) 1984, 1988

Very few campaigns are written to be movie scripts. In 1984, Gary Hart, a relatively unknown Senator from Colorado ran against big names like John Glenn, Walter Mondale, and Jesse Jackson. Mondale, who eventually lost to Reagan, reportedly considered Hart as his vice presidential pick before nominating Geraldine Ferraro.

Four years later, a more experienced Senator Hart returned to the scene and was immediately greeted with rumors that he was having an affair. He responded by unequivocally declaring that he wasn’t having an affair, that he and his wife were happily married, blah, blah, blah, and then tied it all up by daring the press to follow him around.

Wait, what? OK. He must be serious.

Hart’s quote to the New York Times was, “Follow me around. I don’t care. I’m serious. If anybody wants to put a tail on me, go ahead. They’ll be very bored.” Unfortunately for Hart, the dare appeared in the Times on the same day that an exposé appeared in the Miami Herald proving that he was having an extramarital affair. Oops.

Candidates have come back from worse than that, though, and Hart was determined not to let a little fooling around ruin his chances at the White House. But that was before the next article, featuring pictures of Donna Rice, the woman implicated in the affair, sitting on Hart’s lap on a yacht called Monkey Business came out. A yacht called Monkey Business? That’s just too good to be true. Of course, the media ate it up (and Hart with it).

The Senator attacked the press for “unfairly portraying him,” a sentiment with which former President Richard Nixon was only too familiar: Nixon wrote Hart a letter, complimenting him on “handling a very difficult situation uncommonly well.” What a compliment.

Hart withdrew his candidacy under media pressure and went to Ireland for a few weeks, but returned and campaigned through several primaries under the slogan “Let’s let the people decide!”

He received about 4% of the vote and withdrew again, this time for good.

- Jimmy Carter (D-GA) 1976, 1980

But… Carter won.

Yes, in one election and by 2%.

In 1976, Carter ran against Gerald Ford, the man who had pardoned Richard “I am not a crook” Nixon. Ford had already lost the support of the Democrats for pardoning their arch enemy, but he also managed to lose any hope of Republican support by granting amnesty to draft-dodgers. In fact, a young Ronald Reagan came within spitting distance of unseating an incumbent president at the Republican Party’s convention in Kansas City, MO (that hasn’t happened in almost 200 years).

So no one liked Ford. So what?

So Ford’s authority as president was anything but certain, he had enemies to his left and his right, and, in a debate, he showed off his lack of skills by saying, “There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe,” to which the moderator replied, “I’m sorry, what?” His Federal Reserve’s policies lead to runaway inflation and he presided over the highest unemployment rates the country had seen since WWII.

Wow. Carter must have won in a landslide!

Not exactly…

After the Democratic Convention, Carter held a 33% lead in the polls. However, after Playboy published an interview with Carter in which he admitted to having “lusted in my heart” for women other than his wife, Carter’s lead began to slowly collapse like a flan in a cupboard. Ford closed the gap in debates and by attacking the former Georgia governor’s experience.

When the polls closed on November 2, 1976, no one was sure who would win. Carter had lost his 33% lead and Ford looked like he might win a second term, despite being a thoroughly underwhelming candidate. NBC didn’t announce that Jimmy Carter had won Mississippi (and passed 270 electoral votes) until 3:30am on November 3. The 27 states that Ford won were and remain the most states won by a losing candidate.

In 1980, Carter lost to a resurgent Ronald Reagan in a landslide, 489 to 49. Of course, Carter wasn’t to blame for the Iranian hostage crisis, but the voters held him accountable anyway. The stagflation that had continued as a result of Ford’s economic policies was also attributed to Carter, but his campaign did very little to shift the blame. Carter lost the popular vote by nearly 10 points – a crushing defeat by any standard.

- This post was originally hosted on the Tufts University blog Jumbo Talk